- Home

- Kate van Hooft

We See the Stars Page 8

We See the Stars Read online

Page 8

I turned a little to watch out of the corner of my eye, and saw Cassie push Ms Hilcombe’s hand off her shoulder.

‘Fine,’ she said, loud enough that everyone around her could hear, and Ms Hilcombe went back and sat down at her desk, and stayed there until the bell rang for recess. That morning we’d handed in our poster, which I’d done most of by myself after I’d been to Cassie’s house, and we got to see what everyone else had done. Sarah and Nicole’s had a big peace sign drawn in glitter, and they’d also put a white hand and a brown hand held together over a picture of the Australian flag that they’d cut out from a magazine. Ours didn’t have any glitter, but Cassie’s drawings of the flowers and machine guns were coloured in bright enough that you could see them from the other side of the room, and my handwriting where I’d written all the words I’d found in the newspaper didn’t look so bad because of it. Cassie was angry, though, because Jeremy’s dad had called the newspapers in the city and he’d got actual copies of the articles I’d seen in the library that I’d written out, and he’d glued them on to his poster, so that ours said the same thing but was harder to read. In the end Jack and Thanh won with their poster, which had the most colours, but also they’d done some of their own writing so that theirs wasn’t words just copied from the paper or from a book, and Nick scoffed loudly when Ms Hilcombe said they’d won it, and said that it was all political.

At recess I followed Cassie into the quadrangle with some extra Vegemite biscuits, and she took them from me without saying thanks. We sat on a tree stump behind the bubblers and watched all the other kids mucking around.

‘Sorry about the other week,’ Cassie said, and she tried to pull her hair back behind her ears but it was too short to stay there. She caught me looking and she smiled at me, but her eyes stayed dark. ‘It’s just, Mum’s got a thing about me having boys over. She doesn’t mind getting creative with her punishments, either.’

I put my hand up to try to help her get the bit around her ear to tuck in, but she ducked away from me. ‘Oi, Vegemite fingers? Keep them to yourself,’ she said, but she was laughing, and when I looked at my hands I realised they had biscuit crumbs and butter all over them.

Nick and Jeremy were playing kickball in the quadrangle, and when Jeremy accidentally kicked the ball close to us Nick ran up to get it.

‘Shit, sorry!’ Jeremy called out, but Nick was already standing in front of us and he had a grin on his face like when he’s about to cause trouble in class.

‘Hey,’ he called out, so that everyone else in the quadrangle stopped to listen. ‘Last night I was watching a movie, and you know what it was called? The Thing from the Swamp, and it was all about this scary monster with a buggered-up hand who came and scared all the people because it was so ugly. It was all warped and melted. It was so scary, Cassie. Did you see it?’

I looked at Cassie and her eyes were closed down to little slits, and she was biting the side of her lip.

‘Also, it had an ugly haircut,’ Nick said.

Cassie flew at him so quick I hardly even knew it was happening, and she had him on the ground underneath her before he could react. Last year there was a fight between two grade six boys and one of them had to go and get his lip sewn back together at the hospital, and everyone knows about Daniel Bradbury who got into a fight with another kid because he said he’d cheated in basketball and Daniel ended up knocking the other kid out and getting suspended for a week.

I wanted to tell Cassie she didn’t have to do it, that her hair didn’t even look that bad, and that she definitely didn’t look like she came out of a swamp. I stood up to show her she could stop it, but there was so much noise, and I tried to take her hand and pull her away but she kept shrugging me off her, and then Nick looked up and called her The Claw in front of everyone, and Cassie turned real red and went at him again. I leant down again to pull her away, but Nick looked at me over her shoulder.

‘You got your little nuffy mate to help you?’ Nick asked, looking directly at me.

I froze on the spot. I wanted to wee.

‘Careful you don’t catch the spaz off him.’

‘Piss off!’ Cassie screamed.

The other kids laughed.

‘Maybe you already got the spaz off him,’ Nick said. He was smiling but his lips were thin. ‘Explains the haircut.’

I tried to go invisible. I tried to turn into air. I stood right where I was, right there on the spot, while it all just kind of played out around me, and I felt heavy in my tummy when the noise came up over the top of me and broke over my head. I looked around at all the other kids’ faces and they were red and screaming. If I reached up and put my hands over my ears I couldn’t really hear anything anymore, like if someone had turned the volume down on the TV and all the light and the colours were kind of mixed up, but then I was dizzy and wanted to be sick and at the same time I tried to be exactly still so that it would wash around all over me, and maybe then I wouldn’t be a part of it at all.

‘Oh shit, he’s losing it,’ someone said, and I felt a push between my shoulders that sent me down to the ground. I landed on my knees and for a second I felt the breath get knocked out of my chest. I could see Cassie scratching and Nick kicking and the two of them rolling around on top of each other, and I could hear the screaming and the chanting of the other kids, and I felt the warm wee on the inside of my legs going cold and stale up against my school pants. It only took a second before the smell of it was out in the open. I looked up and one of the girls was already holding her nose.

Cassie and Nick had stopped fighting and were looking over at me. I wanted so much to go invisible, and I wanted so much to disappear into thin air, and I looked at Cassie and hoped that she would help me. For just a moment Cassie wrinkled her nose and her mouth went tight on one side.

***

Cassie and Nick got detention and I got a pair of shorts from sickbay but they were too loose and real scratchy, and I had to hold them up around my waist. When I got back to class the other kids all held their noses and pretended that I smelt like wee, and I found out that Cassie’s mum had been called and she’d had to come home from work to pick her up.

I didn’t want to go home in different shorts while my proper pants were in a plastic bag at the bottom of my schoolbag, which stank of wee and old banana. I didn’t want to have to explain to Dad or Grandma why my pants smelt like wee and I thought that maybe I could wash them, but I’d need to find a bucket and some soap. The other shorts were scratchy and rubbed on my skin, and it was cold enough now that my legs got covered in goosebumps from the wind. I thought about Cassie’s face with her nose wrinkled up. I thought about wool down to the skin.

When the bell went for home time I stayed a little longer in the corridor, and I pretended I’d lost something so I had to go back, and then when I’d run out of things to pretend to look for I went outside and sat on the steps near the office and waited until everyone was mostly gone. I saw Davey go down the lane by himself bouncing his football, and I saw Rohan and Jeremy get into the car with their mum. If you waited until it was dark enough you could go down the lane and then the next lane without anyone seeing you, and you might even get back to the house with Grandma still in the kitchen and not seeing you come in. Superman held my schoolbag for me, and he had his cape to wrap it up in so that you could hardly smell the wee.

The door to the office opened, and I went still as a statue for a second in case it was one of the women from the front desk.

‘What are you still doing here, Simon?’ Ms Hilcombe asked. ‘Don’t you want to go home?’

I looked up at her but didn’t say anything.

‘I heard about the incident in the playground this morning. I’m sorry.’

I felt my face go red and my cheeks get hot. I didn’t want Ms Hilcombe to know about it. I didn’t want anyone to know about it but especially not Ms Hilcombe, and especially because I didn’t want it to have happened at all.

She came and sat on the step n

ext to me. ‘I know today was no good, but things are still going better for you, I think,’ Ms Hilcombe said. ‘Cassie’s a good girl. Okay, she’s a bit wild, but maybe you might calm her down a little.’

I thought about Cassie swinging on the clothesline and nearly pulling it out of the ground, and the lemons rotting on the side of her driveway. I thought about how her mum worked late and how her dad wasn’t there. I thought about Grandma’s house without Grandpa in it. I thought about Mum.

We sat together without saying anything for a while. I watched the trees sway. The leaves were starting to go red and orange and some had already fallen off, and as it got darker I felt the cold hard and sharp on my cheeks.

‘You know it’s funny, Simon,’ Ms Hilcombe said, ‘but I always worry that I’ll say the wrong thing around you.’

I squinted my eyes when I looked at her, and there was just enough sunlight coming in over the tops of the trees that I could see little bits of dust and dirt in the air swirling around in front of her mouth when she spoke, and the waves her voice made in the air pushed them further out towards me, and when I breathed in I sucked them into my lungs and my blood, and I felt the warmth of them there start to grow hot and pink against the cold.

‘I mean, not that I suppose you would think less of me,’ she continued. ‘It’s more that…you make me choose my words quite carefully. Like, I want to think carefully about what I say to you. It’s a rare thing to be around someone who just listens. I kind of like it, even though you make me work so hard.’ And she laughed then, but not in a mean way. If Cassie had been there she would have slapped me on the back and called me a name, and it would have felt sort of similar but still different, and Ms Hilcombe made the warm go pinker with just her voice in the sunlight on the steps.

‘I think you’re pretty brave,’ Ms Hilcombe said. ‘I think you’re very brave, Simon, and I’m sorry you have a hard time with the other kids.’

If it got much darker Dad might come home and realise I wasn’t there, so I stood up and put my bag on my shoulder. I smelt the wee and the rotten banana, and I put my hand on the top of the shorts and held them up. Ms Hilcombe stood up with me, but she just stayed still and watched as I went through the gate. I walked down the lane and then the other lane, with my bag on my shoulder and Superman behind me airing out his cape to get rid of the smell. I didn’t look back, but I didn’t really have to, because even after we’d walked down my street and were standing at our letterbox, I still just knew that she was there.

Eleven

My feet took me over the railway line and up around the corner and then on to Cassie’s street, and it didn’t really take very long at all. The grass was longer than the last time I’d seen it, and there was no car in the driveway, and the sheet in the window had come away so that I could see all the way into the lounge room, and when I knocked on the door I could see Cassie coming through to open it. I could see her look right at me, and I could see that her face was wooden and empty and that she didn’t even smile.

‘You probably shouldn’t be here,’ Cassie said, and she didn’t open the door very far. ‘Did anyone see you?’

I turned and looked up and down her street, and there was no-one around, and the wind was getting cold and it smelt like it might rain again. She looked at me, and then she looked up at the sky, and for a second I could see the reflection of the clouds floating across her eyes.

‘Okay, come in,’ she said. ‘Wipe your feet, though, and don’t bloody touch anything.’

Cassie’s bedroom was smaller than mine, but she didn’t have to share it with anyone, and her bed was jammed up against the window so that you could put your head on the pillow and look up at the clouds, and there were no posters on her walls and only a few books on the floor and it was hard to step inside without standing on some clothes. We sat on the bed and Cassie tucked her legs up underneath her, and I squeezed my hands into fists and sat on them.

‘Mum works in Manerlong on Saturdays,’ she said. ‘But she could come back for lunch, so…just be careful, I guess.’ From Cassie’s bedroom window you could see over the fence and out to the paddock next door, which was full of tall but nearly dead grass, and a tree on the top of the hill that had branches so dry they looked like they’d just crumble if you tried to climb them.

‘So was everyone talking about me after the other day?’ she said.

I nodded.

‘This town is so bloody small, everyone knows everything. I went for a walk to the shops yesterday and Mrs Lyon told me off for going out when I’m grounded. Right in the middle of the milk bar? I wanted twenty cents worth of lollies and I got told off instead. Just, excuse me for living?’ Cassie laughed but she didn’t seem happy, and then she looked at me and her face was all dark. ‘Nick’s a dipshit and he would have kicked the living shit out of you if he’d decided to,’ she said.

I nodded, because I knew that it was true, and I kept thinking about Cassie’s face when everyone had smelt my wee, and I kept thinking about Nick calling me names in front of everyone, and I kept thinking about the scratchy wool of the shorts that I had to hold up with one hand.

‘I can’t believe you pissed yourself though, man—that was the best,’ she said, and she was laughing. ‘I was getting killed by that arsehole. If you hadn’t done that he wouldn’t have stopped and I would have got my face punched in.’

She’d put a couple of pins in it, but her hair still looked uneven, and there was still a longer bit on one side of her face. It looked like one of her ears was lower than the other, and it made her whole face seem lopsided.

While she sat on the bed I went to the bathroom and found some scissors in the drawer, and I walked back into the bedroom with them, but when I held them out to her she started backing away up the bed.

‘The hell are you doing with those?’ she said, and she had her shoulders wedged right up into the corner. I held them out to her but she wouldn’t take them, she kept shaking her head. I climbed on the bed with them and crawled over to her on my knees, but she pulled her knees up under her chin and wrapped her arms around them, so that she was hunched over into a ball. I reached out and put my hand on her shoulder, and she looked me right in the eyes. I held on to her, and for a second I just waited. It didn’t sound like she was breathing, but she bent her head forward, and I cut her hair so that it was even on both sides, and when I was finished I took the hair that I’d cut and put it in her right hand, and I put the scissors in her left.

‘Thanks, Numpty,’ she said. She put her hair and the scissors on the table beside her bed, and she relaxed back with her shoulders against the wall, and we sat watching the tall grass wave in the wind in the paddock next door, and every now and again I’d hear her sniffle, and if I turned my head towards her quick enough I could catch her wiping at her face.

Later we sat out in the kitchen while Cassie made some sandwiches out of bread and cheese, and the sun got low over the window and the light went all golden, and our shadows on the kitchen wall grew tall enough that they reached all the way to the ceiling.

‘Numpty, do you reckon it’d be possible to pack everything you’d ever need in one bag? I mean, so that you could carry it all around with you all the time?’

I thought about my dresser and my bed and the cup that I have my milk in, which has a little chip on it just beside the handle that kind of tickles and kind of pinches the skin when you rub it over your lips.

‘Nah, you probably couldn’t, hey,’ Cassie said. ‘You’d have to think about what to take, and what to leave behind. I’d want to take some of Dad’s records, but then you’d have to have a record player to play them on.’

She took a long drink of her orange juice, and it left a little ring of pulp around her mouth. I rubbed the back of my hand over my mouth too, but it came back clean. ‘Nan’s got a place in the city, and sometimes I think about going to live with her. Like I could go to a big school with heaps of other kids and not just little shits like Nick. Plus, Nan doesn’t

talk to Mum so she wouldn’t tell her that I’m there, and they have their own pool and they’re right next to the train so you can just get a ticket and go wherever.’

In the backyard, the Hills hoist was leaning even further, so that if you put a long beach towel on it it’d get dragged down through the grass.

‘What do you reckon about Hilcombe?’ Cassie asked with her mouth full of cheese.

I shrugged my shoulders but I smiled, and I kind of wanted it to look like I was happy to feel whatever Cassie felt about Ms Hilcombe, but also that I thought she was okay and that I hoped that Cassie thought she was okay too, so that we could agree.

‘I think she’s a cow,’ Cassie said, and I felt my shoulders drop. ‘She’s got it in for me, for sure,’ she said. ‘Also, I see her walking around the shops all the time, and she’s got a dog that looks like a little rat.’

I took another bite of my sandwich, but the cheese had gone sour and I couldn’t make it go down. I chewed until there wasn’t enough spit anymore, then I waited until Cassie wasn’t looking and I spat it out into the bottom of my shirt.

‘Did you know she lives around the corner from you?’ Cassie said.

My eyebrows shot up and I couldn’t really stop them. ‘Mum used to clean the house for Mrs Garner before she carked it. Hilcombe moved in and put a massive gate up, first thing, and told Mum not to worry about cleaning it anymore. Tight-arse bitch. Place probably stinks like dog shit. I’ll show you where it is.’

***

Ms Hilcombe’s street goes like this: white wooden house on the corner, brick house, brick house, empty block with a tree growing on it and lots of weeds, brown wooden house, brick house, Ms Hilcombe’s house, brick house with a big window, second brown wooden house, brick house on the corner. All along there are trees and grass and the road is kind of curved so that Ms Hilcombe is in the middle and all the other houses wrap around hers, and if you climb the tree in the empty block you can see into her backyard, and if you stand on the nature strip on the opposite side of the road you can see the front.

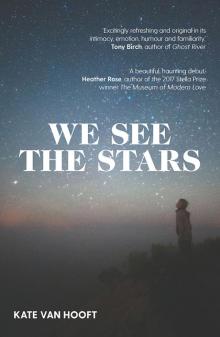

We See the Stars

We See the Stars