- Home

- Kate van Hooft

We See the Stars Page 7

We See the Stars Read online

Page 7

‘Or what about, right, if you could get all the lollies in the whole shop? I’d put them under my bed and keep them there for just me to have,’ Davey said. He went quiet for a minute, and you could hear the radio from the milk bar just loud enough to get the music but not any of the words. ‘But you could have the milk bottles,’ he said.

If you put your head back you could see the tree lines just above the roof line of the post office, and past that the sky and the blue of it. If you didn’t let your eyes squint down into slits from the brightness you’d be able to see the little zipping pins of light in your eyes from the blue, and you’d be able to follow them around the inside of your brain, so that you were seeing inside yourself, even to the bits that were pink and red and moving, and you could be wrapped up in your own body, with a layer between you and your skin.

‘Is that your teacher?’ Davey said, and I turned to see Ms Hilcombe coming down the street. She had her frizzy hair and big skirt on, and she was looking down at the concrete as she walked but with a little bit of a smile on her face. Davey bounced the ball real loud in the gutter and she looked up at us, and her smile got a little bigger. I felt the honey drip right down to the bottom of my tummy, and the bees already inside my legs and heading down to my toes.

‘Simon, is this your brother?’ Ms Hilcombe asked.

Davey pulled the sock up on his leg.

‘Lovely day for it,’ she said.

‘Are you the teacher?’ Davey said, and Ms Hilcombe laughed.

‘I’m one of them, yes. You’re in Mr Newman’s grade?’

Davey turned his face back to the road. He didn’t like Mr Newman, but that was okay because nobody really did.

‘And what are you two fine gentlemen doing today?’ Ms Hilcombe asked.

‘I broke my ankle,’ Davey said. ‘But now I can play footy again.’

‘Ouch, that sounds like it must have hurt,’ Ms Hilcombe said.

‘I nearly died at the dam,’ Davey said.

My tummy felt heavy, and I couldn’t really look at Ms Hilcombe without then looking away real quick.

‘Did you?’

‘I could have drowned,’ Davey said. He bounced the ball a few more times.

Ms Hilcombe watched him. ‘I broke my arm when I was younger,’ she said. ‘Came off a horse.’

‘Did you nearly die?’ Davey asked.

‘No, just did a number on the bone,’ Ms Hilcombe replied. ‘Not been on a horse again since. Dad wanted me to run the farm when he got older, but…I just couldn’t bring myself to.’

‘Y’know the milk bar?’ Davey said. The purple and blue burn behind my eyes grew big enough that it got even to the back of my brain, and I couldn’t think for the weight of it.

‘That one there?’ Ms Hilcombe asked. She pointed right at it.

‘You can get a half-bag of mixed lollies for fifteen cents,’ Davey said.

‘What a bargain,’ she said.

‘It’s good—the musk sticks are more though. Simon likes those the best but it’s not worth it, hey, Simon?’

Ms Hilcombe looked down at me, and her hair stuck out enough on both sides that they were nearly even, and her shadow on the ground made her look three times as tall.

‘How’s the project going with Cassie, Simon?’ Ms Hilcombe asked. ‘I know she can be a bit fiery. Are you two getting together to work on your poster soon?’

I nodded, and felt the blush up the outsides of my cheeks.

‘That’s good,’ Ms Hilcombe said. ‘I hoped you’d do well with it. Y’know, it’s funny, but Cassie reminds me of you a bit sometimes. I’m…I’m just really glad it’s going well.’

Davey sighed and started bouncing the ball again, and he looked up at me from under his eyelashes and rolled his eyes.

‘Well, I’d better leave you two to it,’ Ms Hilcombe said. ‘Don’t want to be seen with a teacher on your holidays. Could ruin your reputations.’

Davey nodded and I put my hand up to wave goodbye, and she waved back at me, and she smiled. I had tingles up and down my insides, and my brain was blue and purple from the burn, and I still felt the warm from it, and the light, and the good.

After she was gone Davey leant back again on his elbows, but the clouds were coming in thicker now, and there was only a little bit of sun left.

‘Do you reckon if I kick real hard it’ll break again?’ Davey said. He looked down at his ankle, and poked at it through his sock. I reached out and put my hand on it, but it only felt like bones and muscle, like when you’ve picked all the meat off the barbecue chicken but you still have to carry it out to the bin. I took the warmth from Ms Hilcombe, and her smile when she waved, and I took it from my chest and my face and along the back of my neck, and I sent it down into my hands so that they were pink with it, and I pushed so that it crossed over to Davey and made him feel better through the skin.

‘Thanks, Simon,’ Davey said. ‘That feels nice.’ I pulled my hand back. I put it in my pocket. I twisted my finger into my palm.

‘It’s cold, hey,’ Davey said. He started to stand up. ‘Grandma’ll probably let us in again now,’ he said. ‘It’s nearly lunch anyway. Oi, shoelaces.’ He pointed to my feet; the laces of my left shoe were undone. I leant down to tie them, and just as I was doing the loop around the bunny ear, a bag of musk sticks dropped next to my foot. I heard Davey yell, and when I looked up he’d just caught a mixed bag, and his eyes were bright enough that they were shining, and there was a shadow of frizzy hair walking away up the street, three times as tall as the real thing.

***

To get to Cassie’s house means walking in the opposite direction, and instead of going across the road and down the lane and then down the other lane, you walk up the hill along the side of the school and then down past some older houses and a few paddocks and then across the railway line and up and over another hill with a smaller paddock where there aren’t even any animals or anything growing, and then you get to Cassie’s street, and her house is the third on the left from the corner. It’s got a wooden verandah and the curtains in the windows are just sheets so if the lights are on you can see people moving around inside.

Cassie’s house is set back from the road, with a big paddock on one side, and a slope that leads to a couple more paddocks out behind. When you walk up the driveway you have to go past a bunch of lemon trees, and if you look at the ground as you walk, you can see dead ones on the ground, and the smell of rotting comes up from them and into your nostrils, so that if you try to hold your breath and get all the way to the house in one go, you can get pretty dizzy, and you might even need to sit down on the verandah for a bit.

Cassie stood in her lounge room. There were clothes on hangers that hung off doorframes, and piles of sheets and towels in baskets on the ground.

‘Mum’s not here, but when she gets home she does people’s ironing,’ Cassie said when she caught me looking, and it made me blush. ‘Don’t touch anything, okay? If you get it dirty she’ll have a fit.’

I’d already taken my shoes off at the door, and there was a hole in my left sock where my big toe could poke through. I kept my fingers curled into my palms and held my knuckles tight and closed.

‘Here, come out the back,’ Cassie said, and then she led me through the kitchen and out onto the back porch. Her backyard was really just a small paddock with a big tree in one corner and lots of weeds and the grass almost up to your knees, and in the middle stood an old Hills hoist that was kind of crooked and leaning over to one side.

‘This is where I practise,’ Cassie said. She took off running down the porch steps and out into the yard, and when she was nearly about to head straight into the clothesline she jumped and grabbed on and the whole thing turned and she was swinging out and around. She stuck one leg out in front of her and the other straight, and her hair caught the sunlight and went flying out behind her. She looked strong and her arms were stretching long and thin, and she held on until the clothesline stopped turning and then

she dropped off it back into the grass.

‘This is my dance partner,’ Cassie said, and she pointed at the clothesline. ‘Until I make it to the city, he’ll have to do.’ She was smiling and kind of shiny with sweat and I stood on the porch watching while she jumped up and took another swing. The clothesline kept listing over to the side when she swung around and then rocking back to the middle when she made a turn, and it looked like it was going to come loose and that she was going to fall, and when it really leant I held my breath and wanted to close my eyes but then she’d always pull back up again, and one leg would be out and one leg would be behind her, and each time she dropped down she’d land with hardly any noise at all.

‘Come on, we can sit up at the table and get this bloody poster over with. I’ll show you Dad’s records, too,’ she said, and she waded through the long grass back to the porch.

Cassie showed me how to drop a record on the big round plate and then put the needle in the groove so that the music could start, and she let me pick a record except I didn’t really know any bands so I just picked one, and I played a song with guitars and a man singing, and it was basically the best thing I’d ever heard. And when it was over, and the next song came on, Cassie showed me how to put the needle back to the start so that we could listen to the first song again, and we started dancing around and around in the living room, and there was a whole lot of noise that I could feel right down deep in my chest.

Afterwards, we sat on the floor and panted and sweated, and Cassie lay with her head on the floor and her feet tucked up under my legs. I could feel her toes in her socks brushing up against my skin and it gave me little prickles all the way up to the top of my shoulders. We tried not to get too close to the piles of laundry, and the clothes on the hangers hung down just close enough to nearly touch our heads.

‘Will you come see me when I’m a famous dancer?’ Cassie said.

I felt a laugh roll up through my belly, and it gripped onto my throat until I let it go.

Cassie smiled at me. ‘Here, get up,’ she said, and she pulled me by my arms so we were standing opposite each other. ‘I’ll show you how to bow. All dancers do it.’

She folded one foot over the other and stuck her arm out straight from her body, then leant forward bending over double at the middle, and swept her left arm under to come up and meet the one on the other side.

She peeked up at me. ‘Okay, give it a go,’ she said, and she stood up straight to watch. I put one leg over the other, and when I bent I kept my head up so I could see her face. I wobbled a bit and lost my balance, and I had to put my feet the right way round again so that I didn’t tip into the laundry.

‘That’s pretty crap, but we’ll work on it,’ Cassie said. She bowed to me again, and her legs stayed straight and crossed over, and she didn’t wobble even when she was bent over almost double. I gave it another go, and I kept looking at my toes this time, but I still had trouble getting the right balance, and when I looked back up she’d screwed up her nose.

‘Nup, no good. Maybe you could just carry my bags for me when I’m famous.’ She laughed.

On the last day of school for the term, Cassie had told me how to get to hers from the school gates. She said she’d be home on Thursday but that her mum would be out at work, and that that’d be a good time to come and do our project and listen to her dad’s records. She said I should come at lunchtime and she’d make sandwiches. She looked me right in the eyes and said she was sort of looking forward to it, actually. Then she’d gone red all the way up to the top of her ears.

We sat on the floor for a while, even after the music had stopped and it had gone quiet enough that you could hear the wind whipping around the paddocks. I thought that maybe Cassie was asleep, but I didn’t want to look in case I moved and woke her up. I wanted to put my hand in her hair and feel the warm in it. I thought about wool right down to the skin.

Cassie stirred and sat up a bit, and I realised it was nearly ready to get dark.

‘You hungry?’ she asked, and I shook my head. ‘Not even for Vegemite? I can put it on toast for ya.’ She was up and moving towards the kitchen, and I shivered when her body was gone and the cold got in again.

From the kitchen you could see out to the backyard, and then over the fence and into the empty paddock. There was gold light coming in from the window, and a bit of it shone right on the back of the wall behind the pantry. There was a cross on the wall there, with Jesus hanging off it by his hands. You could see his ribs and his toes.

’Don’t mind Jesus,’ Cassie said, when she saw me looking at him. ‘Don’t piss him off either—he’ll know about it.’

He looked up from his cross and stared down right into my eyes, and there were tears on his cheek. I blinked, then looked away.

Cassie shoved a couple of stacks of newspapers off the table and let me sit down on it, and our legs dangled off the ends. Her shoelaces were undone and her socks didn’t match, and mine were the same and sat tight over my ankles.

‘This town is so small, Numpty,’ she said. She took a bite of her Vegemite toast. I took a bite of mine.

‘Mum keeps talking about moving somewhere bigger, because out here you can’t get enough work when there’s not enough houses to keep clean. But on the other hand she reckons it’s cheap enough that we could live here forever even on her shit wage, so long as the rent doesn’t go up or the plants don’t shut down.’

The Vegemite was salty across the top of my tongue, and she’d used so much butter some of it got stuck to the roof of my mouth. I tried to push it back down again without using my finger, but I couldn’t roll it forward enough, and the saliva was just making the bread softer, so in the end I reached in and flicked it down with my nail.

‘Charming,’ Cassie said, then she laughed at me with her mouth open and bits of crust fell out onto the floor.

A flash of light through the front window stopped her, and then suddenly it was time to go. Cassie jumped up from the table and was pulling my plate from my hands, and she was rushing our two plates over to the sink to run water over them.

‘Oh shit,’ she said, and the water ran off the plates and down onto the floor, and when I went over to mop it up with a tea towel she grabbed me by the shoulder and pushed me out of the room.

‘No, Numpty, you need to go,’ Cassie said in a hiss. ‘Oh shit, shit.’ She ran over to the record player to turn it off. ‘Mum doesn’t let me have people over. She’ll chuck a fit when she sees you. Plus you’re a boy!’

A swarm of bees flew out of their honeycomb and stung their way out along my veins.

‘Go out the back, you have to go out the back!’

But I couldn’t move and my legs weren’t working and there was no strength left in them anymore.

‘Where are your bloody shoes?’ she hissed.

And then the front door opened and we just froze.

A woman came in. She looked like Cassie except a bit taller and with her hair tied back. She was wearing a big apron and carrying a bucket and a mop.

She stopped when she saw me, and the mop dropped to the floor with an empty thump that woke another swarm that joined up with the others and started stinging up and down my legs.

‘Hi, Mum,’ Cassie said. For a second Cassie’s mum just stared at her, then she turned to look at me. My blood had to push past the bees to get through, and it made them angrier to get caught up in the tide of it.

‘What’s your name?’ she asked me.

My tongue was heavy and I felt my jaw muscles go tight. I looked at Cassie, but she didn’t look back.

‘What’s your name?’ Cassie’s mum asked again. ‘Don’t be rude.’

‘He’s Simon, from school.’ Cassie’s voice was so quiet I almost didn’t hear. I nodded my head because I thought it might help. ‘We were working on a project,’ Cassie explained.

Cassie’s mum’s face was blank, but her mouth was tight and the corners dragged the skin around her lips down. She put the mop against th

e wall and took her apron off. It made a mess of her hair when she pulled it up over her head.

‘In your room, please,’ she said. ‘I’ll deal with you later.’

Cassie didn’t look at me but I watched as she backed away down the corridor. I only stopped watching when she’d completely disappeared into the dark of it.

Cassie’s mum turned to me. ‘You got a home?’ she asked.

I nodded. I felt sick in my tummy and I really wanted to wee.

‘Go to it,’ she said. ‘Don’t come back.’

I walked down the driveway past the lemons, then past the small paddock without any animals in it and past the school and then down the lane and across the road and down the other lane, and when I turned into our street Superman was sitting on our letterbox. When I got to our gate he hopped down and held out his hand to me, and I took it and it was warm. We flew up into the air and up and over my house, and over the school and over the cricket oval, and up over the town so that you could see the main street and the post office and the milk bar, and then higher up still until the town was just a cluster of little buildings surrounded by fields and trees and cows. Then higher, all the way up past the clouds and into the sky, all the way up through the atmosphere, all the way up until you could see the curve of the Earth and the stars and the mountains, and not any of the houses at all.

Ten

When we came back from school holidays all Cassie’s hair had been cut off, except that it wasn’t very even, so there were little bits sticking out over her ears and around the back of her neck. When she walked in Jeremy asked her if she’d lost a fight with a lawnmower, and all the other kids laughed. She put up her middle finger, and it stopped them laughing for a little bit, and Jeremy went red enough that I could see his neck go all blotchy even from my desk on the other side of the room.

During class that morning, Ms Hilcombe let us do some reading, and when it was quiet and everyone was busy, she came up behind Cassie and put her hand on her shoulder.

‘Are you okay?’ Ms Hilcombe whispered.

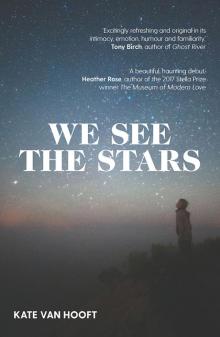

We See the Stars

We See the Stars