- Home

- Kate van Hooft

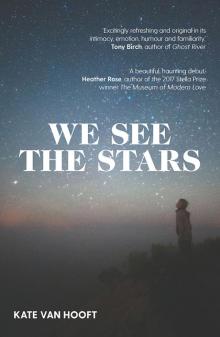

We See the Stars

We See the Stars Read online

Kate van Hooft was born and raised in Melbourne to an Aussie mum and Dutch dad. She lives with her husband Paul D. Carter, also a writer.

Kate has a BA in Creative Writing from Melbourne Uni, a Master of Communications from Deakin, and is now completing a Master of Social Work. She has worked for more than ten years in student wellbeing and disability support in secondary and tertiary education. As a professional in the disability and education sector, Kate has become passionate about youth mental health and the way current therapeutic trauma frameworks can inadvertently pathologise children, meaning ‘they are not always listened to’.

We See the Stars is her first novel.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace the holders of copyright material. If you have any information concerning copyright material in this book please contact the publishers at the address below.

First published in 2018

Copyright © Kate van Hooft 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:(61 2) 8425 0100

Email:[email protected]

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76063 252 6

eISBN 978 1 76063 650 0

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Hugh Ford

Cover photo: Tðnu Tunnel, Stocksy #108905

for Paulie

and KB

and Mum

Contents

Zero

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Eleven and a half

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Sixteen and a half

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-two and a half

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Minus one

Minus two

Acknowledgements

Zero

It gets dark quicker than you think it will, and even with the torch it’s hard to see where we’re going. Superman is sure that if we can get to a clearing we’ll have a better look at where we are, and where the mountains are. If you hold the torch steady enough and straight out you can see the trees and the ground in front of you, well enough that you don’t have to worry so much about stepping in any holes, but it’s heavy and my arm is getting tired and I’m worried about the batteries going flat.

I find a log and sit on it, and even though Superman wants to keep going I make him rest as well. It’s important that he gets enough sleep tonight because tomorrow’s probably going to be another big day of walking and I’m not really sure how far we still have to go.

‘I couldn’t find any water,’ Arnold says. His pyjama bottoms are dirty from being dragged in the mud, and there are sticks in his hair from where he’s brushed up against the branches, and through his paper skin you can see the hole where the heart used to be, but now there’s only black, and stillness. ‘Did you really not bring any food?’ he asks.

I shake my head. I feel the burn in my eyes and I rub at them.

‘Back when I was a lad you got taught these things,’ Arnold says. ‘If you couldn’t live off the land, you couldn’t live.’

I shrug my shoulders, and I feel the soreness from where the bag’s been cutting in. I squeeze my fingers into fists and let them out again and I taste the sour down the back of my throat.

There are birds in the trees and if you look up with the torch you can just catch them before they duck out of the way. Their eyes light up green and red from the bright of it. They talk to each other in whispers under their beaks.

‘Do you think Ms Hilcombe’s alive?’ I ask Arnold. Superman’s wrapped his cape around his shoulders and he’s tucked his legs up under his chin. He’s blowing hot air into his hands and rubbing them.

‘Maybe,’ Arnold says. ‘The important thing is that you keep looking.’

‘Can you hear her?’ I ask.

‘I could for a while, but she’s gone quiet now.’

I don’t have a warm enough jumper, and if I use the torch too much I’ll run down the batteries. If it’s quiet I can hear the little crinkles in the bones when I move my neck. The longer we sit here the longer Ms Hilcombe is tied to a chair in the farmhouse, or the longer he’s holding her head under the water in the creek, or the longer she thinks that I’m not coming to save her.

‘But it’s late, son, and an old man needs his rest, eh?’ Arnold starts to settle down with his back to a tree and his arms tucked up into his armpits so they don’t fall away to the sides.

There are some bits of sky that don’t have any clouds, and you can see right through to where the stars would be if there were any.

‘What if we can’t find her and no-one else can either?’ I ask.

Arnold’s already snoring, and the sound of it makes little waves in the air that come up over the ground and in under my eyelashes. When I blink it feels heavier, and there’s rough bits of dirt stuck to the inside.

I look at Superman. ‘I promised,’ I say.

He points up at the darkness, where there is only total black. ‘Is that the Big Dipper?’ he asks.

I feel the squeeze in my chest let go a little. I put my head on my knees. I close my eyes.

One

You have to be careful when Grandma drives you out to the dam, because the seats of her car get so hot that you need to bring your towel to sit on if you don’t want to burn the back of your legs. Getting out there takes about half an hour going in the opposite direction to Grandpa’s hospital, and if you’ve forgotten something to sit on the next best thing might be the street directory, but that’s slippery to sit on if you’re sweaty as well, and Grandma yells at you if she sees because she says it makes the pages go wrinkly.

Davey had been asking to go to the dam ever since Dad got him a new beach towel for Christmas and told him he’d take some work time off before school went back so he could use it. The dam is kind of in the middle of nowhere, which means that kids come from all around and not just town to come and swim, so if you’ve got a new beach towel it’s the best place to take it and show it off.

Davey wound the window down, and the air came rushing from his side over to mine, and I felt it push up into my face and lift the hair up off my head, so that for a second it was hard to breathe any air in, and the noise of it nearly covered the sound of the engine.

‘Do you reckon you’ll swim with the other kids today, Simon?’ Grandma asked, and I shrugged.

‘Rohan’s going to be there with his cousin

from the city,’ Davey said, and Grandma smiled at him in the rear-vision mirror.

‘That right?’ she said. ‘Do you like Rohan, Simon?’

‘Rohan’s cousin has his own pool at his house,’ Davey said. ‘They can go in any time.’

‘Bet it’s a pain to keep up,’ Grandma said.

Another car came up behind us and then went around with its engine real loud. I closed my eyes and felt the sound of it stick all sharp and red to the collar of my T-shirt. Some of them were kids from the high school in Manerlong. The summer after this one I’d be going there, too.

‘I wish Dad was coming,’ Davey said.

‘You know he’s got work,’ Grandma told him, leaning over to change the radio station but only getting static. I turned around and looked at him in the back. He had bright yellow zinc across his nose.

Davey sank back into his seat. ‘Dad’s a good swimmer, hey?’ he said.

‘He was a great swimmer,’ Grandma replied, and I turned to face the front again. ‘He won lots of ribbons, a heap of them, in school.’

‘Does he still like swimming?’ Davey asked.

‘It’s not something we’ve ever talked about, love.’ Grandma switched the radio off altogether.

‘Rohan says his dad’s going to get them a colour TV,’ Davey said, and I saw Grandma roll her eyes. She started driving faster, and the wind got loud enough that you couldn’t hear anything else Davey tried to say.

That afternoon there were heaps of cars, and you could see them lined up even from the bottom of the hill. We found a spot under an old tree in someone’s paddock where the fence had come down, and I watched Davey’s footprints in the dirt in front of me so that if I put my feet in them you could see that even though mine were still bigger his were catching up, and that if he kept growing but I stopped, one day he’d be the taller one and everyone would think he was the one who was a year older.

At the top of the hill you could look down at the dam and see where the little kids were splashing in the shallow end and where the older ones from the high school had waded out to the far side. They bobbed in the water, and the girls wrapped their arms around the necks of the boys, and every now and again one of them would throw a girl off so that she’d go splashing head first underneath, and her scream would get cut off when her mouth filled with the water and the mud.

Davey stood next to me with his hand over his eyes, and when he saw Rohan in the water he waved to him.

‘Hey, do you need this?’ he said. He pulled my puffer out of his pocket, but kept it half hidden under his T-shirt so Grandma wouldn’t see. I took a breath in and felt the air push all the way down into my chest. I shook my head. He bent down and tucked it under the corner of his new beach towel. I heard Grandma’s footsteps coming up behind me, and I moved over a little so that my foot covered the puffer.

‘Want to get into the water today, Simon?’ Grandma asked me. Davey ran off ahead to meet up with Rohan, and he didn’t look behind him, and he didn’t say goodbye. ‘Just go and paddle with the little kids, then,’ Grandma said when I didn’t respond. ‘Can you do that at least?’ She turned and found a spot to sit in under a tree, where a bunch of other women were reading magazines and a man with a hat pulled down over his eyes listened to the cricket on his radio.

The dam is the only place to really cool down since they took the water out of the pool in Grandma’s town to put out fires last summer, so on hot days you can go there and half our school is paddling around in the deep bit, and most of the kids from Manerlong as well. As I stood at the edge and shielded my eyes to look for Davey, I could feel the sun burning on the back of my neck and the water real cool on my ankles. The little kids in the shallow end were putting their faces in up to their noses and blowing bubbles along the top, and the mud from the bottom was all churning so that you couldn’t really see where to put your feet, and if you got all the way into the water the dirt would get kicked up and inside your bathers, and also in through your nose and your mouth, and when you swallowed you’d take all the dirt in, into your guts and then into your blood, so that if you stood on a rock and got cut open it would come out thick and brown, and full of worms.

‘Simon!’ Davey yelled, and when I looked up I could see he was with Rohan and a couple of other boys from his class. He was standing waist-deep in the water, and his shoulders were already brown with freckles, and if you took a pen and connected them all up you’d have a little map of how it went when the skin stretched out and over his bones. He waved for me to swim over. I felt my knees go a little bit blobby, and I shook my head.

‘C’mon, Simon,’ Davey yelled.

The other boys were watching me, and one of them nudged the other, and then they smiled with their teeth all crooked and not in a row. I shook my head just a little and sat down in the water, so that it covered halfway up my legs if I stuck them straight out in front of me. The other boys kind of laughed, and I saw Davey slap the water a little.

‘Your brother’s weird,’ Rohan said, and the words carried over the surface and along the air, and then inside the curl in my ears. Davey turned away from me so that I couldn’t see his face.

Rohan did a dive-bomb from the top of some rocks and the splash went up so high that it made little waves up to the bank all the way on the other side of the dam.

Next to the rocks some girls sitting on the bank were laughing, but then one of them shrieked as another boy came up behind them and grabbed at her top, and then quickly ducked away back into the water. One of the girls stood up, and I saw that it was Cassie. Her hair was tied up tight at the top of her head, and when she shouted at the boy she waved her hands around so that you could see the one that was all purple and melted at the ends.

‘Oi!’ she yelled, and the sound of it bounced over the water and up into the tree branches, where it got stuck on some of the leaves. ‘Did you just put a worm down this chick’s top?’ She was pointing to the girl sitting next to her, who was screaming and pulling at her clothes, and even from where I was standing you could see she was trying not to cry.

The boy jumped to hide behind Rohan, and Rohan was just laughing, and Davey was too, and Cassie was chasing them both further into the water, where it was already up to Davey’s chest.

‘Don’t let her touch me with her zombie hand!’ Rohan yelled, and ran to hide behind Davey, who slipped when Rohan pulled down on his arms. They both went under and for a second all you could hear was the little kids blowing bubbles in the shallow end, and the leaves falling into the water from the wind. Rohan came up first, spitting water and shaking it out of his hair. Cassie was still yelling, and the other boys were laughing from the top of the rocks, and it took a second for Rohan to turn around and realise Davey hadn’t come up yet, and another couple of seconds while all the sound around us got sucked out of the air.

‘Davey?’ Rohan called.

All the other boys stopped swimming, and even Cassie stopped yelling.

‘Davey?’ Rohan called again.

He looked over at me, and all the sweat up and down my arms mixed with the air from the breeze so that it made little grey clouds that hung around over my shoulders, and when I rolled them the air moved with them so that it made a little storm, and the lightning was crackling down through my elbow and out into the air from my fingernails, and the thunder was rolling down from my belly and into my legs, and even though Rohan was waiting for me to do something I just kept staring at the water and waiting for Davey’s face to appear.

I heard footsteps run up behind me, and then Grandma’s papery hands were on my arms.

‘Where’s Davey?’ she asked. I looked up into her face. ‘Where is he, Simon?’ she yelled, so that the noise of it shoved the air up and into my face, and I had to close my eyes from the push.

Rohan was thrashing around in the water, trying to see the bottom through the mud and the dirt.

‘Jesus, Simon.’ Grandma pushed me out of the way and dived straight into the water.

People were pulling their kids out of the shallow bit, and some of the girls were crying.

‘They’ve lost a boy,’ I heard a woman say, and when I turned to look at her she went red. She was holding on to a little kid in togs who had zinc on her nose just like Davey.

I turned back to watch for Davey to come up out of the water. Time went still, and the trees stopped swaying in the hot wind, and the birds froze in mid-air and just hung there in the sky, and the water stopped rippling where Rohan was standing in it, and if you looked you could see your perfect reflection, caught there in the dark and the mud of it, with the clouds behind your head not moving, and the sun high up behind them and never going to set.

Grandma kept swimming, and Rohan kept diving under the water, coming up to say it was too hard to see, and then over the top of the water there was a howl, with pain shredded through it, and then Grandma was swimming off towards the bank on the other side of the dam, and the howl turned into crying, which turned into Davey, yelling at the top of his lungs as Grandma pulled him through the reeds. He was real pale and his eyes were shut tight, and when she carried him out of the water you could see that his ankle was bent nearly all the way through in the wrong direction.

‘Get the stuff!’ Grandma yelled at me.

I stood up to my ankles in the mud. There was no way I could make my legs move.

‘Simon, get the fucking stuff, for Christ’s sake!’ She pushed past me with Davey in her arms, running down to the path that led out to the road.

I heard one of the girls laugh and I looked over and saw it was Cassie. She covered her mouth with her melted, purple hand.

Two

Grandpa sat up in bed with the newspaper on his lap, but he didn’t read anymore. He said the words always got jumbled up when he tried to look at them, and if he wasn’t paying attention they’d just run right off the page. When the nurses brought the paper to him they’d always ask if he really wanted it, and he’d always say he did. Then he wouldn’t look at it; he’d just tuck it up under his arm and let his sweat smudge the ink onto his skin. Sometimes he’d forget the paper was there and he’d let it fall, and then he’d see all the black splotches and say the nurses were hurting him. He’d point to the ink down his arms and howl until a doctor came and calmed him down.

We See the Stars

We See the Stars