- Home

- Kate van Hooft

We See the Stars Page 2

We See the Stars Read online

Page 2

‘This is exactly what I told them,’ Grandpa said, and he was looking at me from the bed. He picked up the paper and pointed to the words with his finger and the skin was thin enough that you could almost see through to the bones. ‘You mark my words, it won’t be the end of it.’

It was getting dark but Grandma and Davey were still off getting Davey’s ankle fixed. I kicked my legs out from my chair and back down again, so that my toes dragged along the lino. They folded under my foot when I pulled them backwards, and I could feel a little pull on the skin if I rolled them around in a circle. I was still in my bathers, and there was mud stuck under my nails.

From Grandpa’s window you could see the main road leading out of Manerlong, as well as all the little streets that went off it. If you turned left at the pub and followed the road around you’d get to Grandma’s place, and if Grandpa was ever especially bad she’d send us back there, giving us a two-dollar note to get something from the hospital canteen on the way. Davey would always get a can of Coke, but I liked raspberry lemonade. Davey always laughed at how the red stained my teeth and lips; he said it looked like I was wearing lipstick. Sometimes I’d chase him around making kissing noises, and the lady behind the counter would tell us to go.

I heard voices in the hallway, and then footsteps coming up fast. I stood up from my chair and stood by the window. Davey came through the door first, with a cast on his leg and crutches, looking white and quiet. Grandma came in next followed by a nurse. Davey hopped over towards me, and I gave him the chair.

‘You’ll get used to them, Davey,’ Grandma said, and I saw Davey turn to look out the window.

‘How’s this one, then?’ Grandma said. She went to sit next to Grandpa on the bed.

‘He doesn’t want to cooperate today,’ the nurse said.

‘What if I took him home for a bit?’ Grandma asked.

‘Probably best if you let us handle it, hey?’ the nurse said.

Superman stood up in the corner to stretch his legs. He had a stethoscope in his hand that was wrapped up around his neck, but each time he tried to use it his cape got caught in it, and he had to pull at it to try to get it free.

I glanced over at Davey, who had his chin resting on the windowsill and his nose right up against the glass. When he breathed out you could see little clouds form on the window, and he was writing rude words in them with his nose.

‘He just gets so muddled with all the medication,’ Grandma said, and she looked for a second like she might start to cry.

Grandpa’s shirt was hanging open, and so you could see all the old skin and saggy bits across his chest, and Grandma was trying to get him to close it but he kept trying to grab at her arms.

‘Come on, love,’ Grandma said. ‘A bit of decency this late in the afternoon, hmm?’ He caught her arm and held it there. There were tubes that went in through his skin and hooked up to the veins so that if you touched him with your finger he was hard from where the cold got in.

‘Simon and David are here,’ Grandma said.

Grandpa turned to look.

‘You two!’ He pointed at us, and the lightning shot straight through my legs and into the floor from my toes. ‘Tell the officer the Turks have the left flank!’ he ordered. ‘Go on—run!’

I was stuck on the spot. There were grey clouds gathering heavy around my throat and I held my mouth shut tight to keep the thunder from getting out.

Grandpa was just yelling now, and the nurse was trying to push him down onto the bed. Grandma told us to wait outside. I pulled Davey up by the hand and helped him hop out of the room. We heard Grandpa howling for us, but we kept walking.

***

Before he got sick, Grandpa was good at reading stories before bedtime. He did all the voices, and when he was talking for a girl he would put his voice up real high and prance around the bedroom. Sometimes he’d even put a towel on his head so that it was like he had long hair, and Davey and me would laugh so hard that my tummy hurt and Davey’s eyes would start to water, and Grandma would come in and tell us to be quiet and Grandpa would pretend that he was upset to be told off but really he was just laughing underneath too, and then as soon as Grandma was gone he’d put the towel back on and pretend to be her.

Davey sat in the corner of the waiting room, but he didn’t want to play with the toys. I let the bottom of the plastic chair make dents in my legs, and if I didn’t move them much I couldn’t really feel the pain of it. Superman got himself a drink out of the little water fountain, but he tried to be quiet and was careful not to slurp.

Grandma came out of Grandpa’s room, and her eyes were red around the edges.

‘We’re hungry,’ Davey said.

‘I just want to stay until he’s settled,’ Grandma told him.

Davey didn’t say anything, but I felt him wriggle a little in his seat.

‘Alright, love,’ Grandma said. ‘Stay here and I’ll see if the canteen is still open.’

‘Can I come?’ Davey asked. He stood up, but just toppled over because of his cast. He reached out and put his hand on my shoulder to steady himself, and I could feel his weight through my shoulder but there wasn’t any burn. Grandma sighed and nodded, and Davey took off down the corridor after her, with his leg dragging a bit behind him. His crutches were still on the ground by his chair.

I went to stand by the door of Grandpa’s room. It was quiet again, and when I entered I was careful to walk on my tippy-toes.

Grandpa was awake, but he didn’t look happy, and there was a bit of drool coming from his mouth and down onto the front of his shirt.

‘Simon!’ Grandpa said when he saw me. ‘Come over here where I can see you.’

I walked over to him, and he pulled me down onto the bed to sit next to him. I felt the burn on my skin where his hand held onto it, but when I tried to pull away he just held on tighter.

‘You ever let yourself get stung by a bee?’ he said.

I felt a crackle of lightning at my elbow where he was holding it. I nodded. Once I’d been out with Mum to get the groceries, and it was so hot that the sun was making me feel dizzy. Davey was in the stroller so I couldn’t fit, and Mum bought me an icy pole for the walk home. Halfway home I’d had most of it, but there were sticky bits on my hands from where it had melted, and when I wasn’t looking, a bee came and got me right on the middle of my hand and I started to cry. Mum told me it probably liked the sweetness. She shushed me and held me and I could smell the sweat from under her arms and around her neck. Davey was crying in the stroller, but she parked him under a tree and held me. We counted all the things that we could see that were red, and then blue, and then green.

‘Ah, then you’re done for,’ Grandpa said, and he shook his head at me. ‘I’m sorry, Simon, but that’s it for you.’

A crack of thunder rolled out over my shoulder, and I felt the lightning shoot down from my neck and out through my ear.

‘Where did it get you?’ Grandpa asked, and I pointed to my hand.

He held my hand in his and when I looked at his I saw the lumpy blue veins running all through it.

‘You’ll never get them out once the stinger’s in—little known fact about bees.’ He put his head back and stared up at the ceiling for a while, and then his eyes closed but his hand still gripped my arm. I only pulled it free when his breathing had slowed right down, and I had counted all the white things I could see, and then all the grey.

‘That was your brother in the water, Simon,’ Grandma said from the doorway.

When I turned I saw she was holding a sandwich in a bag. I felt warmth where Grandpa’s legs pushed up against mine.

‘You didn’t even try to help,’ she said.

A little baby bee, with a stinger only just sharp enough to get through the skin, flew around in my chest and started looking for a place to build a honeycomb. It pushed its way up against the flow of the blood, and eventually got up towards my heart.

Grandma turned away from the doorway, and I knew tha

t I was supposed to follow, but my feet were still covered in mud and reeds and when I tried to move them they were too heavy.

‘It’s dangerous, is what it is,’ she said, and then she was gone.

I reached out to Grandpa and I squeezed his hand real hard in mine. It didn’t wake him, and I gripped his hand so that the memories would travel down my arm and flow through my skin into his, so that they would flow into his blood and into his nerves and then into his brain, and then my memories would get all mixed up with his ones, and he could have them there in his head where he needed them, and he would know who we were when we came back to say goodbye.

***

That night, Grandma sat out on the back porch with Dad smoking cigarettes while Davey read one of my old comics and I lay with the sheet pulled right up to my nose and pretended to be asleep. If you opened the window over Davey’s bed you could hear Grandma and Dad’s voices, but it was hard to get any of the words. Most of the time they were quiet, and apart from them and the bugs in the trees there wasn’t any sound at all. Davey had his cast propped up on a pillow, and he was rubbing at his eyes to get the sleep out. He rolled over to look at me.

‘Stu said this house is cursed,’ Davey said, ‘and that everyone talks about us behind our backs.’

I felt something heavy settle in my tummy. I swallowed but I couldn’t get enough spit going, and it made me feel sick along with the weight in my guts.

‘Why don’t you ever say anything?’ he asked, and his mouth was tight and small.

I put the pillow over my head and felt the warm of my breath on my face. I heard Davey turn his lamp off and roll over, and after a little bit I also heard his snores.

I tried to do some counting, but I couldn’t hear enough things to count more than four or five, and it was too hard to see any colours in the dark. Superman opened the bedroom door and signalled for me to get up, and I followed the ends of his cape down the corridor so that I wouldn’t trip.

I trailed my fingertips along the wall and felt the spot where I’d put a dent in it with Davey’s cricket bat when Grandma had told us we had to sit at the table to eat dinner and that we couldn’t have a picnic in the front yard, and I’d had one of my angries and Mum wasn’t there to count.

I took another couple of steps and felt the doorway for the spare room, but the door was closed. The wood was smooth and it was cooler than the plaster. I scratched it a little bit with my fingernails, and it tickled enough that the door made a little squeak and giggle. I felt along to the gap in the wall leading into the kitchen. I let my left hand swing into the darkness, then quickly pulled it out in case I touched anything that I didn’t know was there.

The lino turned into carpet, and I could feel the join along the strips of the wallpaper, and then my right hand went to Mum’s doorway, and I leant my ear against the wood in the darkness, and waited for the sound of it. There was orange light in the living room from the streetlight, and it made the walls look orange, and when you held your hand up in the light of it, your shadow got reflected onto the front of the door.

Mum took a breath in, and through the wood I heard the bed creak. I opened the door and waited for her to see me, but she was rolled onto her back. Her eyes were open, but you could only tell for sure if they moved when she blinked. You could still hear the sound of her breathing, but that was pretty much all.

The mattress had a dip in the middle so that when we lay next to each other we kind of fell in together, and I put my hand in hers to stop from crashing into her side. There was dust in the air and I breathed in hard enough that the skin got caught under my ribs, and I felt a wheeze in my throat that made me scared it was closing. We looked up at the roof, and the orange light through the curtains made lace on the walls.

With my other hand I reached up to the ceiling, and I felt my arm stretch under my skin so I could get all the way up to the height of it, and when my hand touched the white it was cold and smooth under my palm. It didn’t want to move but I kept pushing at it, and after a while it made a grinding noise as it shifted, and I wondered for a second if there was too much dust and worried that it would fall into our mouths and choke us, but the ceiling came loose with a bit of a shove, and I folded the roof out to the side and onto itself, and then we could see all the way up to the sky.

From where we were lying you could see the stars, and they were little white lights in the darkness, and the cold from the night was there with us still in the room, and it smelt like when you’ve blown the candles out on your birthday cake and the smoke is white and spirit and curling upwards into the air. Mum watched the stars twinkling, and she smiled when I showed her the Southern Cross. She pointed to the three stars lined up in a row. I took a breath and felt the air push all the way out of my chest.

‘Is that the Big Dipper?’ she asked. Her eyes were bright from the light in them, and they shone in the darkness more than any of the stars in the sky.

Three

I had the window open in the bedroom to let some air in, and even though I didn’t really want to I could hear Davey and Rohan in the back room. Davey was sitting on the floor with a pillow under his cast, and when I walked through to get a glass of water they both went quiet. They just kept looking at the cards in their hands, and Davey pretended to be thinking. I knew he was pretending because he put his hand on his chin and started scratching at it, which is what Dad does when he’s trying to concentrate, except Dad actually has hair to scratch at on his face.

‘Oi, no, you have to skip a turn,’ Rohan said, and from my bed I could still see them in my head sitting on the floor in the back room.

‘Nah, I took two cards,’ said Davey.

‘Yeah, you take the cards, but then you have to skip.’

‘That’s not how we play it.’ I could hear the whine starting in Davey’s voice.

‘Well, you play it the dumb way,’ said Rohan. ‘You have to skip.’

I heard Davey sigh. ‘What about if I play my wild card?’ he asked.

‘Nah, you still have to wait—and now I know you have one, dickbrain.’

‘I don’t have one, though,’ Davey said, and I could tell he was lying because his voice went high. ‘I was just asking.’

‘Bull,’ Rohan said. There was a moment’s silence, then: ‘This is boring. Can’t we go play cricket or something?’

‘Can’t with this on,’ Davey said.

I heard the sound of him scratching at the cast. The little sharp noises made the skin under my ears itchy, but when I tried to tickle it with my fingers I couldn’t reach in far enough, and after a bit I realised the itch was actually on the inside.

‘Do you want to play another round?’ Davey asked.

‘I should probably go home,’ Rohan said. ‘Mum’s taking me to Manerlong to get a new uniform for school next week. Hey, maybe you could play with your brother.’ I heard him snort out a laugh.

‘What about tomorrow?’ Davey asked. ‘Come back then. Dad’ll be home and he might take us for a drive.’

‘He never does, but, hey?’ Rohan said.

I heard Rohan walk down the hallway towards the front door. Davey followed, but his footsteps were all out of whack from the cast and it made one foot louder than the other.

When I was younger and Davey wasn’t even in school yet, I was friends with a girl who lived down the road and across the cricket oval. We used to go to kindy together and sometimes I’d go to her house afterwards, especially if Mum wasn’t coming to pick me up because she was looking after Davey or she was tired. Tamara had a paddock out the back of her house and in it she had a pet sheep whose name was Tilly, and Tilly liked me a lot. I liked to put my hands in her wool and feel all the way down until I got to the skin and the muscle underneath. She used to make a little grunting noise and it used to make me laugh and her wool was real oily but I liked it down underneath my fingernails, and even though Tamara’s mum used to make me wash my hands and sometimes told me off for going and getting them dirty, I didn’t mi

nd because I felt the wool on my fingers for ages afterwards, and sometimes there was still the smell of it, even after I’d gone home.

Tamara’s dad went to the war, and when he came back with his leg blown off they moved to the city, and Tilly got sold to another farm a few towns over. For a little while after she was gone you could stand on the edge of the paddock and see where she liked to eat the grass the most, and where she liked to stand. When it all grew back, then when it went yellow in the summer, then when it grew so high it was up to the top of the fence, if you closed your eyes down to little slits and watched the top of the grass where the sky was, and if you waited for the wind to come and make it sway, you could almost make out that it was her with her legs crunching on dead grass while she pushed her way to you, and her wet nose finding the cup of your hand, and your other hand resting on her back and the heat of it, and you could feel the heaviness in your tummy where the lightness used to be, and you could remember what it was like when she looked at you, and that when she was gone it made the corners of your mouth turn down and ache, and you could feel what it was like when you had something and then you lost it, and you could feel her wool right down to the skin.

When I went out to the back room I could see the stacks of cards on the floor, and the cushion that Davey had rested his cast on. Even though the blinds were half closed to keep the sun out, there was still enough light to see the colours of the cards, and when I peeked I saw that Davey did have the wild card, but he also had the Draw Four. If he’d played it he might have won, but then that would have meant the end of the game. I heard him thumping back up the hallway, and his face was red with a bit of sweat dripping off it, and even though it was harder to walk he still refused to use his crutches, and there were little marks in the carpet where the cast had dug in on his way up and down.

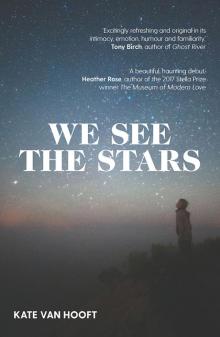

We See the Stars

We See the Stars