- Home

- Kate van Hooft

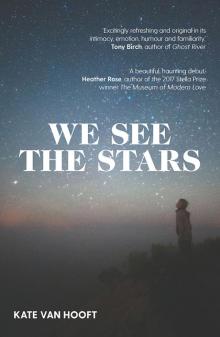

We See the Stars Page 12

We See the Stars Read online

Page 12

I took a big, deep breath. If you tried not to listen you could pretend that you couldn’t hear the wings. There were feathers all in the bottom of my belly, and they got stirred up and into my throat, and it meant that it was dry and that even if you tried to say something it would just all sound like bird. I looked down at the crumbs on the porch near where Cassie’s feet were, and I pressed one with my fingertip so that it stuck to the skin, and then when I had it in between my fingers I pressed down and squashed it into air.

It sounded like a car was coming, and Cassie’s eyes went real wide. ‘Down,’ she said, and she pushed me on the shoulder so that there was a little bit of a burn, and then I was lying with my nose against the verandah and she had rolled away inside the door. I could feel the air in stripes on my face, and if I opened my eyes I could see little strips of ground between all the darkness, and the smell of dirt came up beside the air.

I heard the car go past, and then I heard the silence, and then I felt Cassie put her hand on my shoulder. I sat back up but she wouldn’t settle, and instead she came out and stood on the end of the verandah and looked up and down the street.

‘Do you reckon good people can do bad things but still be good, sort of, overall?’ she asked.

I picked up a few more crumbs with my fingertips and blew them away into the wind, so that if Cassie’s mum came home she wouldn’t know we’d been sitting there.

‘Probably not, hey?’ Cassie kept moving so that her feet were hardly ever in the same place at once, and the air kept pushing her skirt around, and there were crumbs all stuck to the bottom of it. ‘I’m pretty sure it’s just a one-time offer.’

A gust of wind blew up over the verandah, and Cassie’s skirt blew up a bit so that I could see all the way past her knees, and she shrieked and grabbed at it, but I saw a flash of her undies, which were white with little pink flowers on, and it made me blush so hot in my cheeks I nearly had to take my woolly hat off.

‘Alright, perve,’ Cassie said, but she was laughing. ‘Oi, speaking of, is Jeremy okay?’

‘He’s worried,’ I said. ‘He told me about the car.’

Cassie went quiet for a second, and the sun came out a little bit from behind the clouds, and it lit her up from behind so that I could only see the shape of her, and her hair sticking up bright and glowing at the edges around her face.

‘He’s alright, Numpty,’ she said. ‘I know Nick’s a dingbat, but Jeremy’s okay. I trust him.’

She put her leg straight out in front of her and pointed her toes, then bent over at the waist with her arm up over her head. When she pulled herself back up again she was smiling, but she still seemed sad.

‘Hey, Numpty,’ she said, ‘how do you make a tissue dance?’

As I watched she spun around with one leg out in the air and did a little leap, so that she landed on the other leg and only wobbled a little bit to stand up straight again. ‘Put a little boogie on it,’ she said, and she laughed hard enough that I caught it off her.

‘You go,’ she said, and I felt the bird stretch its wings up so that we were bone on bone again, but I swallowed down a feather and thought for a second.

‘You’re too slow!’ Cassie said. ‘Okay, what’s a crocodile’s favourite card game?’

I shrugged.

Cassie was already giggling. She ran up towards me with her arms stretched out. ‘Snap!’ she yelled, and she brought both arms down together over my shoulders like she was biting me in two. I fell back against the doorway and banged my head on the wood, and she laughed even harder when she heard the thump of it. ‘Good one, Numpty,’ she said, and she was laughing so hard her eyes were watering, and after a second I felt the burn spread out and away across the back of my head and into my shoulders, and I laughed too, when I felt the bird settle back down into its nest.

‘Okay, I feel better,’ she said, and she pulled me up off the verandah so that I was standing next to her. I looked towards the paddock next door, which should have had sheep in it but didn’t, and didn’t have any cows or horses either.

‘Hey, did you know that they found a dead body in there?’ Cassie said. I looked over at the paddock to the tree that was dead but still standing up in the grass. The bird raised its head from the nest it had made with the feathers, down in the bottom of my belly. ‘Yeah, it was the guy that used to live in the house across the road.’

I looked again at the old station wagon in the front yard without wheels on, with weeds growing up through the windows where the glass used to be.

‘He was real old, and they reckon he got out of the house one night and went up into the paddock by mistake, and then just carked it right there in the middle.’

The tree in the paddock was black and hollow in some bits, and the man stood on the top branch and looked down at the ground, and the bottom of his pyjama pants kept getting stuck on the branches, and he frowned at the little rips along the hem. He looked up when he sensed me watching. When he waved, his hand was all covered in dirt.

‘You should go,’ Cassie said from behind me, and when I looked back at her she was pulling her jumper tighter across her middle, and it had gone cold again with the sun behind the clouds.

***

After I left Cassie’s I went around the far end of the paddocks and out along the back road, and I listened for any cars coming but there weren’t any, and I felt the bird start to stretch out its wings so that when I got to the street that led back to school I just kept going. If you go around the back way you can actually go in a big circle all the way around the town, and you can get back to your house without having to walk past the school, and sometimes if it’s peaceful enough you can even get all the way home without anyone else coming past in their cars. The thing is, though, that it’s real empty out the back way, and there’s nothing much to look at except your own feet underneath you, and sometimes you can hear the cows in the other paddocks and the trains going through the crossing, but if you sit out there long enough just in the tall grass you can basically pretend that you’re the only one left on Earth, and that all the other kids are gone, and that you get to be all quiet and still in just your own ears and skin.

That way takes you back around the houses and to get to my street you have to turn in at Ms Hilcombe’s. It was real quiet, and there weren’t any cars on the street, and I couldn’t even hear Tink in the backyard. I sat down on the ground, just beside a fence made out of wires that were sharp enough to make you bleed, and I rubbed my hands in my eyes until the little pins of light started to dance and swim. I put my fingers in the ground and it was dead and dark underneath, and even when I tried to rub them clean on the grass there was still dirt under the nails.

There were a whole bunch of letters in Ms Hilcombe’s letterbox, and it looked like they were nearly going to fall out. If you peeked into the letterbox you could see that there were at least five, and that there was one that was all folded up on itself, which was making it hard for the others to fit. The thing is that there are snails that live in letterboxes, and their favourite thing to eat is words, and if they’ve had a big meal you have to hold them up to your ear and wait for them to burp to hear what the letters were supposed to say. If I reached in I could just about unfold the one on the bottom, but that also made the others fall off the top and then one slid out onto the ground right down at my feet. It looked different because it didn’t have the whole address on it, it just said ‘Janet’, and there wasn’t even a stamp. When I turned it over in my hands I realised that it wasn’t actually in an envelope; it was just a piece of paper folded up. If you held it up to the sunlight you could see that there was only one word on it, and that it was written by hand, and that it definitely should have been left just exactly where it had been.

If you look through a microscope at a bit of wool, you can look much closer than what you can see with just your eyes, and if you look real hard you can see that the bit of wool is actually made up of even smaller bits of wool, and that they all lock in around

each other and grip on so that the whole thing is made up of the littlest bits. If you put the wool on your skin, like if you rub your face all along it or you drag it along your arm, you can tell all the little bits are there because it itches, and they get locked into your skin and catch, and if you hold it there long enough it all wraps up around you and you get to be a piece of the whole.

Superman and me walked back down the street towards the paddocks, because he didn’t really feel like going home, and school hadn’t finished yet. Superman held the letter, but he had his cape over his hand so that he didn’t have to touch it, because it kind of burnt his fingers a little bit. Also, we didn’t say anything, not even after Superman took the letter from me and read it too, and each time I looked at him he just looked back down the street. The thing about it was that I couldn’t hear any other words in my head except for the one in the letter, and I could feel it pushing right up against my teeth, and if I opened my mouth it would fall out onto the ground and be in the air again. If Superman held the letter shut it would mean it was trapped and that he could make it go away as soon as we thought of a way how.

There’s lots of things you’re not supposed to do, because bad things happen if you do them. You’re not supposed to breathe in when you go past a cemetery because all the ghosts will come in with the air and get trapped inside you, and their breath will get caught up with yours and every time you speak you’ll leak a little bit of them. You’re not supposed to open an umbrella inside—even if you’re just standing out on the porch it still counts—and you can’t really be sure if you can open your umbrella unless you’re already a little bit wet. You’re definitely not supposed to step on any cracks, and more than anything you’re not supposed to steal. Superman held the letter but he held it through his cape so his skin didn’t touch it, and when he walked he kept looking down at it, and I got all full up with bees, and if you looked up into the sky it was empty, without even sun or even clouds or even air.

We ended up back near Mr Justfield’s, just near the railway line and with only one house across the road. Mr Justfield’s cow was in the paddock by his house but all the curtains were drawn, and there weren’t many pellets in the trough by the gate. As we came up along the fence Mr Justfield’s cow came towards us, with her head real low to the ground. When she got to the fence she looked up at us, and I saw the brown around the middle of her eyes, and she leant her head over so that I could rub my hand up and down her long nose. She blinked her eyes real slow then, with my hand rubbing up and along the fur, and when she opened one eye up you could see your reflection deep down in the dark of it.

‘Hello,’ I said. I could see her long tongue, and it was pink and blue underneath, and it kind of curled around under itself when she reached up to lick the letter. It was still warm from my back pocket, and when she bit down on it I didn’t want to look, and even when she swallowed it there wasn’t any sound.

Fifteen

That night I got in the bath and sank down so the water went over my neck and my shoulders and face. I sank so low that not even my nose was sticking up out of the water, and so low that I had to squeeze my eyes closed to keep it from getting in. I could hear that there was water getting out from under the plug, and I knew that I couldn’t stay under for very much longer, but the bees were really loud in my ears, and I kept thinking about the letter, how dry and sharp it was in my fingers when I fed it to Mr Justfield’s cow.

Grandpa had old records that he used to keep in milk crates next to his couch, and if you asked him to he’d put one on loud enough that you could feel the beats all the way through your chest. Grandpa’s music wasn’t like Cassie’s records with loads of guitars. It was older music that Grandpa used to listen to when he was just a kid, and it sounded like you lived inside a black-and-white movie. Sometimes we’d go over there and Dad would sit in the backyard and have a beer, and Davey and me would go inside and watch the cricket, and when there was a tea break Grandpa would get up and put something on. He’d try and pull us up from our chairs to dance with him, and when we wouldn’t get up he’d dance around the room with a cushion from the couch, and hold it tight up to his chest and whisper things to it, and Davey would laugh so hard he’d cough until he couldn’t breathe.

The thing about Grandpa’s music wasn’t even about the instruments, or the music, or even the sound of it. The thing about Grandpa’s music was that it belonged to him, and that it could have been basically anything except that it was from Grandpa’s living room, and it was coming over on the same air that you and him were breathing, and it was inside your ears just at the same time that it was inside his.

My chest felt heavy like someone was sitting on it. There was a cockroach under the sink, and it kept running along the walls to try to get out of the bathroom. It had a hard shell across its back, with just its little legs sticking out the sides, and the hard shell kept anything from getting in. I watched as it went behind the toilet, then around underneath the sink again. I could see its little feelers twitching along the floor, and after a while it found the drain and slipped down it.

‘Simon!’ Grandma called from the kitchen. ‘Are you still in there? Davey needs a go, too.’

I got out, and when I put the towel around myself it was tight over my chest and my back. The bird stopped flapping and settled down in the nest that was sitting at the bottom of me, and was made from the feathers of its own hollowed-out bone wings. I went to the bedroom and got into my pyjamas, but I couldn’t put the towel back because Davey was in the bathroom, so I went down the corridor instead and stood outside Mum’s door.

The trees in the front yard were getting too many branches, and it meant that hardly any light from the street got in through the front window. If a breeze came along the little bits of orange light danced around it. I could feel my breath coming out warm under my nose.

I kept my ear tight to the wood and tried to hear over the buzz. Cold air came out from under the door and gave me goosebumps along my arms. I squeezed my hand into a fist, and I tapped out the letters onto the wood with my knuckles.

S-I-M-O-N.

I put my ear back to the wood to hear if there was any response, holding my breath so I didn’t miss it.

I tapped again.

S-I-M-O-N.

There were little scratching noises on the other side of the door. I heard a couple of light taps on the wood from soft fingertips.

H-E-L-L-O, they said.

I turned the doorhandle slowly so that it wouldn’t creak.

Mum lay on the bed with her hair spread out on the pillow. Her eyes stared up at the ceiling. She blinked every now and then, but other than that she didn’t really move. I got up onto the bed beside her, and I put my ear against her heart and heard the beat of it. I felt her chest go up and down with her breaths. I saw her toes flex backwards and forwards.

I moved my head up to her shoulder. I put my nose in her neck, behind her ear. She didn’t stir, but I could still hear her heart beating. I took a bit of her hair and wrapped it tight around my finger.

‘What do clouds wear under their shorts?’ I asked.

It was real quiet, except for Grandma on the phone in the back room and Mum’s breath coming in and out of her nose.

‘Thunderpants,’ I said.

A car drove down the street, and Mum kept staring at the ceiling, and the cold got in under my clothes and sent goosebumps all up and over my arms.

‘Why was the sand wet?’ I asked.

Mum’s pyjamas were on the floor, and there was a glass with water in it that had gone real cloudy.

‘Because the sea wee’d,’ I said.

Superman picked something up from the floor and held it up for me to see, and when we saw that it was a bra his cheeks went red and he put it back where he found it.

‘What did one hat say to the other hat?’ I asked.

Superman rolled up a pair of socks and put them down on the end of the bed.

‘You stay here, I’ll go on ahead

,’ I said.

‘Simon?’ Grandma called, and the sound of it ran down along the corridor and in through the door. I jumped off Mum and ducked down so that I was on my knees beside the bed, and when I heard the door creak open I crouched down even lower so that the dust in the carpet went up and inside my nose.

I saw Grandma’s feet poke around the edge of the door, and I heard her breath mixed up with mine. I crouched on the floor and tried not to think about sneezing. For a real long time everything stayed just like that.

The thing about Grandpa’s music is that it wasn’t just about what was on the record, it was also about all the other sounds. Like how it sounded when Grandpa’s shoes danced on the carpet, or how it sounded when he tried to hum along, or even how it sounded when Davey started laughing, and it all got mixed up with the music so that if you listened to it again without them you’d probably be surprised they weren’t there.

‘You in here again, Simon?’ Grandma asked, and I squished up against the bed. If she came through the door and around to the side of the bed she’d see me for sure. I held my breath, and Superman put his hand over his mouth.

‘Simon, please,’ Grandma said, but quietly.

After she’d closed the door I waited a while, till I heard her footsteps go back up the corridor, before I got up and onto my knees. Mum turned her head to watch me, and even though it was dark you could still see that her eyes were red.

‘Why was the pony coughing?’ I asked.

She turned to face the ceiling again, and after a little while she closed her eyes.

‘He was a little hoarse,’ I said.

I picked up my towel from the floor and reached out and put it over her, down her body and along her arms, and with both hands I squeezed it tight over her skin. I held it there until I could feel that it was warm, and until I could see that she was sleeping, and until her skin was all mixed up with mine, deep down in the cotton and the wool.

We See the Stars

We See the Stars